- Home

- Elizabeth Goudge

My God and My All Page 30

My God and My All Read online

Page 30

Francis lay still in worship. He heard the first flutings of the birds and knew that the sky was lightening. It was no longer a grief to him that he could not see the sun, and would not again see clearly the beauty of earth that he loved so well, for like his suffering it had been given to him as a pledge of heaven. It was passing from him now, for it had done its work, preparing him by its reflections and shadows of blessedness for the heaven of God’s love that was to come, encompassing him about with songs of deliverance. Yet in its passing he felt he loved it more dearly than ever, adored God in it and for it as never before and was infinitely grateful for all that God, through the beauty of the world, had given him and taught him. He had loved his brothers and sisters the birds and animals and flowers, but now with heaven so near his thoughts turned not so much to them as to those greater creatures of God, the sun and moon, the stars and winds and waters, and mother earth herself. Joy mounted in him, up and up with the song of the lark as she sprang toward the sun. When the warmth of the new day was on his face, and the life of the convent began to stir, he called the brothers that he might share his joy with them, for he never hoarded joy. When they had gathered round him Francis rose from his bed and began to sing.

Not now in the language of the troubadours, for the earth and sun were to him the earth and sun of Italy, the fire the one that burned under the pot in the homes of the poor. He sang in Italian, in rugged rhyme, as the peasants sang their laude, and the simple song that had grown out of the night of pain was so full of joy that it has become one of the deathless songs of all time.

O most high, almighty, good Lord God, to thee belong praise, glory, honor, and all blessing!

Praised be my Lord God with all his creatures, and specially our brother the sun, who brings us the day and who brings us the light; fair is he and shines with a very great splendor: O Lord, he signifies to us thee!

Praised be my Lord for our sister the moon, and for the stars, the which he has set clear and lovely in heaven.

Praised be my Lord for our brother the wind, and for air and clouds, calms and all weather by which thou upholdest life in all creatures.

Praised be my Lord for our sister water, who is very serviceable unto us and humble and precious and clean.

Praised be my Lord for our brother fire, through whom thou givest us light in the darkness; and he is bright and pleasant and very mighty and strong.

Praised be my Lord for our mother the earth, the which doth sustain us and keep us, and bringeth forth divers fruits and flowers of many colors, and grass.

Praise ye and bless the Lord, and give thanks unto him and serve him with great humility.

The threefold rhythm was still the same, first the solitary darkness of prayer, then the illumination and afterward the practical action. Francis was full of zeal now to conquer men’s hearts for God with song. Having set his canticle to music he sent for Brother Pacifico, his poet laureate, and taught it to him, and to other brothers who had good voices. He planned to send his singers on tour through the world. When they came to towns and villages first a brother was to preach, and then they were all to sing the canticle, and then they were to say to the people, “We are God’s jongleurs; and for that we have sung to you, we ask a reward: and our reward will be that you all abide in sincere penitence.”

Francis was soon given proof of the power of his canticle. While he still lay ill at San Damiano he was told that the bishop and the mayor of Assisi had quarreled. They were no longer on speaking terms and the bishop had excommunicated the mayor. Assisi appeared to be enjoying the quarrel, for no one was doing anything at all to compose it. Francis was grieved and after some thought he made a plan. He added a new verse to his canticle, and then he sent one brother to the bishop asking him to receive the mayor, and another to the mayor telling him to go with his magistrates to the bishop’s palace, and to his singers he said, “Go and sing the Canticle of Brother Sun before the bishop and the podesta and the others who are with them, and I trust in the Lord that he will immediately humble their hearts, and they will return to their first love and friendship.” For love of Francis everyone did what they were told, and when they were all gathered together in the open court of the bishop’s cloister one of the brothers stood up and told them how Francis had composed this canticle in his sickness, and then all the brothers sang it, adding the new verse which Francis had written.

Praised be my Lord for all those who pardon one another for love’s sake, and who endure weakness and tribulation;

Blessed are they who peaceably shall endure, for thou, O most Highest, shalt give them a crown.

The voices that had rung very sweetly in the cloistered enclosure fell silent, and to the everlasting glory of the laity it was the mayor who moved first. With tears running down his face, for he was devoted to Francis, he walked across to the bishop and knelt at his feet and said, “Behold, I am ready to make satisfaction for everything as it shall please you, for the love of our Lord Jesus Christ, and of his servant blessed Francis.” But Bishop Guido was only a few minutes behind the mayor in the movement of charity. Taking his hands he raised him and said, “My office bids me be humble, yet because I am naturally prompt to wrath, it behoves that thou shouldst pardon me.” Then they embraced each other and the quarrel was over.

2

AFTER SIX WEEKS AT San Damiano Francis was able to travel slowly on to Rieti. The rumor of the stigmata had preceded him and he was received with reverence and devotion by the pope and his court, and by the whole city. It was almost as though he had been canonized in his lifetime, so great was the honor accorded him. He was lodged in the bishop’s palace, and here the sick were brought to him that he might pray for them and bless them, and many were healed. But although he was a channel of healing to others the doctors could give him no relief from his own suffering. He was content, knowing that only by bearing pain himself could he be used to set others free from it. It was said of his Lord, “He saved others; himself he cannot save.” That is the way of salvation. There is no other way. And so he bore it gladly, and found great comfort in meditating on the glory of God as revealed in creation. When we think how hard it is even for the best men and women to turn their thoughts outward when they are in dire pain, how absorbed they are by the struggle to maintain courage and patience, we realize what a spiritual achievement this was.

At Rieti he had a great longing to hear the viol played. After his God, music had been the great delight of his life, and it was until the end. One of the brothers looking after him had been an expert violist before he joined the order and Francis begged him to borrow a viol “and bring comfort to Brother Body who is full of pains.” But the brother demurred. He now considered the viol a frivolous instrument and he did not know what people would think of him if he asked for such a thing. They were in the palace of the Bishop of Rieti. Not only was his own reputation as a holy brother at stake but also that of Francis as a saint. All the brothers were very anxious that Francis, the glory of the order, should behave as a saint is expected to behave. They had their anxieties in these days, for unexpectedness was a part of Francis. But he was a humble and good patient and he yielded at once. “Let it be,” he said. “It is better to put aside good things than to give scandal.”

But all that day he went on thinking of the beauty of music, until with the coming of night his thoughts were filled with the thought of the beauty of God. When night was in the midst of her course, and the little town lay still, Francis was alone and awake in the darkness. There was complete silence, very heavenly, and then gently and gradually entering into the silence, music. Someone was playing the viol under his window. The musician touched his instrument with an unearthly skill, and the music sounded now here, now there, as though the player were passing gently back and forth. Yet there was no sound of footsteps, only that heavenly music, such music as Francis had not heard since the angel had played to him on Alvernia. He forgot his pain, for in the place to which the music lifted him there was no sufferi

ng.

But Francis was not happy in a town, lodged in a palace and the center of reverence and adulation, and presently he was moved to the nearby hermitage of Forte Colombo and here he spent the winter. None of the doctors who had attended him had been able to do anything for the disease of which he was dying, but one physician hoped to relieve the agony in one of his eyes by cauterizing his upper cheek. When Francis was asked if he would submit to the torture of this treatment he said peacefully that he had no will of his own about his body but was altogether in their hands. And so the ordeal by fire for which he had offered himself on the crusades was granted to him after all. Not one of the four brothers who looked after him, not even Leo, was brave enough to stay with him through this. They fled and left him alone. Elias, whom he had especially asked to be with him, did not appear, and so by himself he sat waiting and watching while the doctor heated the iron in the glowing heat of the fire. When it was red-hot, and the doctor came to him with it, Francis stood up and looking steadily at the glowing beauty of the thing, he signed it with the sign of the cross and said, “Be courteous to me, Brother Fire, for I have always loved thee.”

He met every challenge of his life supremely well but none more perfectly than this.

The treatment did him no good and they tried opening the vein above the ear, and piercing both ears with a red-hot iron, but the torture in the eye was not made any better by the added agony of the ears. The brothers who died in Morocco can scarcely have suffered more, but Francis remained at peace. One of the doctors told the brothers that he would hesitate to give such drastic treatment to the strongest man, yet this highly strung and dying monk was able to endure. Nothing could quench the joy of Alvernia.

One thing at least he was spared in his dying, for he was not given the modern drugs which can only dull the pain of the body by clouding the mind. His mind remained clear until the end. As his body weakened and failed, his immense vitality seemed to burn all the more brightly in mind and spirit. During this winter of pain he wrote canticles and sent them to Clare, and he wrote letters, begging those to whom he wrote never to forget the reverence due to the Blessed Sacrament. This had always been a matter of great concern to him, for he knew how fatally easy it can be for Christians to get so accustomed to making their communions that they begin to take the humility and graciousness of God’s coming almost for granted, and forget that nothing that can ever happen to them can be as wonderful as this. One of the letters ends with a typical flash of vision. He thinks of the gospel carried to all people everywhere, and Christian bells ringing all over the world. He says to his sons, “And you shall so announce and preach his praise to all peoples that at every hour and when the bells are rung praise and thanks shall always be given to the Almighty God by all the people through the whole earth.”

And so the winter passed and with the spring Cardinal Ugolino arranged for Francis to be taken to Siena, which was renowned both for its doctors and its health-giving air. The cardinal, so hale and hearty himself, did all that his love could devise for Francis in his illness. They all did their utmost to keep him with them for a little longer, and in the stories of these days one can sense the desolation of their helplessness in the face of death. The humble are generally humiliated, and Francis had been cruelly pushed aside by men who owed their existence as members of a great and beloved order, in many cases their spiritual salvation, to him alone. Now, at only forty-two years old, he was leaving them, and they knew at last how great a man he was in his humility, how unique in the power of his love. They would never know anyone like him again and without him the world would be darker and colder and the future full of uncertainty and fear.

Neither the climate nor the doctors of Siena could do anything for Francis and while he was there he had a bad hemorrhage which brought him to the point of death. The brothers who were at Siena gathered around his bed weeping and lamenting, begging him to bless them, begging him to leave them some written message for the order, asking him what was to become of them without him, terribly sorry for themselves and perhaps in a lesser degree sorry for him too in his pain.

Amazingly Francis managed to drag himself up out of his weakness and rally to their need. He bade them call Brother Benedict of Pirato, a priest who was ministering to him in the place of Leo. Why Leo was not with him at this time we do not know but we can be quite sure that only some illness of his own would have kept him away. Brother Benedict came and Francis, at the point of death, dictated to him words which read like a prose poem.

“Write how I bless my brethren who are in the order, and who shall come, unto the end of the world. And since on account of my weakness and the pain of my infirmity I may not speak; in these three words I make plain my will and intention briefly to all my brethren, present and to come; namely, that in token of my memory and benediction and will, they should always love one another like as I have loved and do love them; that they should always love and observe our Lady Poverty, and always remain faithful subjects to the prelates and clergy and holy Mother Church.”

Perhaps the great effort which Francis made to do what was required of him brought him back from death, for when Elias, who had been hastily sent for, arrived, he had rallied. Elias decided that he must be taken back to Assisi at once, for it was immensely important that he should die there. He was Assisi’s own saint and if he were to die anywhere else they might never get his bones back. It is hard for us to realize, in our day, what it meant to a city of the Middle Ages to be in possession of a dead saint. They believed that not only did their patron saint defend their city, their lives and their interests upon earth, but he saved their souls too, for in heaven his prayer procured their eternal salvation. And if he were a miracle-working saint pilgrims would come to his tomb, and that was good for trade. With the bones of a saint in their midst they had the best of both worlds, and they did not scruple to steal a saint if they had not got one of their own. Elias, and Assisi with him, were in a panic that Perugia would steal Francis. This was no idle fear. Years later, when the church of San Francesco was finished and Francis’s coffin had been brought from the first temporary tomb in San Giorgio and secretly buried in the new great church, the knights of Perugia came after dark one night, forced their way into San Francesco and heaved up the paving stones with pickaxes in an unsuccessful effort to find the coffin. Not until centuries later was the secret burying place found, and the space around it opened out and turned into the chapel where today we may kneel and pray before the altar tomb with its candles and flowers. Thus great care was needed in the planning of the journey home. The direct route from Siena to Assisi would bring them close to Perugia, and so Elias decided to turn aside at Cortona and take a longer way around through the mountains. It would be far more exhausting for Francis but that could not be helped. At whatever cost to the saint himself his birthplace must have his bones. For an added security Elias sent a message to Assisi asking that a company of armed knights should be sent to meet them in the mountains, so that if Perugia pounced Assisi could defend her holy property with the sword. There is no record of what Francis thought about all this but he was never too ill to be amused.

The first stage of their journey brought them to the hermitage at Cortona, where later Elias would build the beautiful Celle. Here Francis became ill with dropsy and they had to stay for a while at the hermitage. It was late spring and the thoughts of Francis and Elias must have been carried back to that other spring when they had been here together as young men and Francis had received Elias into the order. They heard again the sound of the tumbling stream, and the birdsong ringing in the woods. Francis was suffering very greatly at this time, yet the story that belongs to Cortona shows him compassionate and humorous as ever. A poor peasant came to the hermitage to pour out his woes to Francis, for his wife had just died and he had no food for his children. Francis had a new cloak which the brothers had just given him to replace one that he had given away to a beggar on the journey from Siena, and this he promptly gave to the m

an, warning him that he was on no account to give it up to anyone unless well paid for it first. At this point the brothers came hastily upon the scene, outraged and protesting. That they should have to procure yet a third cloak for Francis was too much. They held onto the cloak and so did the peasant. Nerved by the command of Francis he said he would not let go of the cloak except for payment down. In the old days of the order there would have been no money in the hermitage with which to redeem the cloak, but now Elias was here and things were changed. With amusement Francis was aware of the brothers reluctantly parting with their few coins and the peasant going happily away. All was now concluded to his satisfaction. The poor man’s children were fed, the brothers were once more united to holy poverty, and he still had a cloak for the journey home.

The Rosemary Tree

The Rosemary Tree The Dean's Watch

The Dean's Watch Linnets and Valerians

Linnets and Valerians Gentian Hill

Gentian Hill B00DRI1ZYC EBOK

B00DRI1ZYC EBOK B008O6ZWTG EBOK

B008O6ZWTG EBOK The Scent of Water

The Scent of Water Pilgtim's Inn

Pilgtim's Inn Island Magic

Island Magic Pilgrim's Inn

Pilgrim's Inn Towers in the Mist

Towers in the Mist Green Dolphin Street

Green Dolphin Street The Bird in the Tree

The Bird in the Tree The Child From the Sea

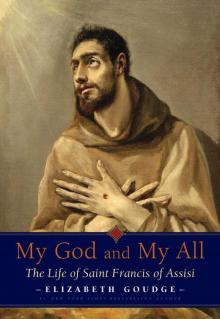

The Child From the Sea My God and My All: The Life of Saint Francis of Assisi

My God and My All: The Life of Saint Francis of Assisi The Little White Horse

The Little White Horse My God and My All

My God and My All B00CKXCNH8 EBOK

B00CKXCNH8 EBOK